William Morris wanted to give the world back its beauty

About the exhibition "William Morris 1834-1896. Art in Everything", on view at La Piscine in Roubaix until 8 January.

He wanted to replace the industrial revolution with the craft revolution. He wanted everything to be as beautiful as it was useful. He wanted to save nature. After reading the article devoted to him by Connaissance des Arts this December, we can be sure of at least two things: William Morris (1834-1896) was a brilliant precursor, an engaging visionary with multiple gifts to whom contemporary design owes a great deal... and you absolutely must rush to Roubaix to discover the exhibition "William Morris 1834-1896. L'art dans tout", on view until 8 January. Or at least immerse yourself in as many documents as possible on his subject, such as the exhibition catalogue or the reprint of his writings. This man who is a writer, painter, architect, textile designer... who has devoted his entire life to the advent of beauty and whose contribution is fundamental to the recognition of the applied arts, is quite simply irresistible!

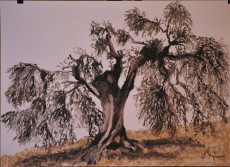

Just imagine. At the age of 17, when the Universal Exhibition was in full swing in London, the young Englishman refused to accompany his parents from the wealthy bourgeoisie that prospered in the Victorian era... on the pretext that the exhibits were too ugly! For him, aesthetic value was already inseparable from any form of manufacture. Progress must not go without beauty. He doesn't want to see railway tracks scarring nature and soulless objects manufactured on a production line, he only wants to see works of art for sale, even if it's to sit on them, to put your laundry in them or to eat in them. The destruction of the landscape in the wake of the industrial revolution upsets him. He prefers to live in his head as in the medieval novels of Walter Scott. His privileged living conditions meant that he did not have to face the horror of the terrible English schools. He spent his childhood frolicking in the countryside, galloping through the forests of Essex, fascinated by nature and its forms. He believes in the utopia of a world where things and people are beautiful.

When he left to study at Oxford in 1853, he met the future Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), and their friendship was to remain steadfast. Together, the two young men discovered the Gothic cathedrals of northern France, the Flemish Primitives and the writings of John Ruskin (1819-1900), a writer, art critic and social reformer who had a considerable influence on Victorian English taste while opposing the economic doctrines of the Manchester School. Convinced that beauty contributes to giving meaning to existence, that men and women should be equally well paid in exchange for their craft skills, William Moris will never cease to implement the new ethical organisation of art theorised by Ruskin, which will add to his personal artistic and literary work a social and ecological dimension that is incredibly relevant today.

From the 1870s onwards, rather than running around art galleries, William Morris joined forces with the socialists to denounce the ruthlessness of the capitalist system, which was destroying all the beauty of the world in its path. To protest against the profit that has "turned the beautiful rivers into filthy sewers" and forced the poor to live in cesspools. He gave lectures all over England, entitled for example "How we live, how we might live". He read Marx very carefully and became a true herald of ecology. "I say it is almost incredible that we should tolerate such cretinism," said William Morris in the 19th century. Alas, he could say the same thing today.

By constantly affirming the importance of all forms of art, whether painting, architecture, graphics, craftsmanship or literature, William Morris worked to restore aesthetic qualities to even the most common objects, producing, through manual work, beauty for use by all strata of society and valuing the rarest skills to counter the prosaic nature of the industrial world. His formal and historical research on Celtic culture and the Middle Ages inspired him and his artist friends, many of whom, like Edward Burne-Jones, belonged to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood founded by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais. "If you want a golden rule that applies to everyone, here it is: don't have anything in your house that you don't know is useful or that you don't think is beautiful," confided the polymorphous artist, who would make his life a fight for the abolition of the borders between fine and applied arts.

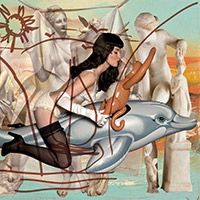

How can one not immediately think of the famous "Art for all and art in everything", the motto of Art Nouveau, notably taken up at the dawn of the 20th century by the artists of the Ecole de Nancy such as Emile Gallé, Louis Majorelle, Victor Prouvé, Antonin Daum, Jacques Gruber and Eugène Vallin. It is fascinating to go back to the origins of this great trend, which seems to be regaining strength and vigour today, finding its foundations in the Arts and Crafts movement that developed in England from 1860 onwards. Architecture, painting, decorative arts and even sculpture... all categories of works of art for sale are concerned. While Edward Burne-Jones painted pictures, Philip Webb created sideboards and Ford Madox Brown designed chairs, William Morris' watercolours and drawings, with motifs directly inspired by nature, became stained glass or wallpaper. All of this was done for the firm William Morris & Co, which he created with his partners, in addition to being the publisher of dozens of masterpieces and the inventor of "fantasy" with his own "fantastico-chivalric" novels.

In 1859, he commissioned Philip Webb to build his first house in south-east London as a sort of manifesto and family home, where he settled with his wife Jane Burden, the undisputed muse of his Pre-Raphaelite painter friends. The entire artistic community flocked to the house and instinctively understood the traditional and unadorned foundations of the Arts and Crafts movement, inspired by medieval architecture: locally made red brick, gabled roofs, chimneys, windows of various sizes, asymmetrical facades... From the interior decoration to the everyday objects, including the furniture and the design of the garden, everything was beautiful and comfortable, illustrating respect for materials and the work of craftsmen. His doctor said at the time of his early death at the age of 62 that he had simply succumbed "to having been William Morris": a man whose exceptional creativity had finally exhausted him.