All of Gilles Aillaud's painting is political

About the exhibition “Gilles Aillaud. Political animal”, on view until February 26 at the Center Pompidou, in Paris.

The work of Gilles Aillaud (1928-2005) initially had a bit of the same effect on me as that of Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899): a priori the representation of animals is not what appealed to me. attracts in painting, but by taking a closer look, and above all by also taking an interest in the artist's life, suddenly it fascinates me! With this difference that the fact that he does not sacrifice to hyperrealism as his predecessor did a century earlier, already made Gilles Aillaud more accessible to me from the start. More likely to please me. His panther heads, blurred like a photograph would have done of a moving beast, interested me. Its lions, its giraffes, its seals... always in captivity and blending into the decor of their cages, could not leave me completely indifferent. This son of an architect, painter but also writer, scenographer and theater decorator, is in truth a formidable political animal. And this is what is wonderfully underlined by the title of the exhibition, intended by its curator Didier Ottinger as a reflection of the concerns of our time: “Gilles Aillaud. Political animal”, on view until February 26 at the Center Pompidou, in Paris.

“Because I love them,” the artist replied to those who asked him why animals had become his favorite theme from 1963-64. Pop Art and the society of spectacle were in full swing, and he began to paint animals alone in zoos, locked in cages, enclosures, glass roofs or behind gates, tending, through mimicry, to blend into their medium. It is therefore easy to imagine that the desire to produce works of art to sell on the contemporary art market was far from being his only motivation. The precision brought to the treatment of subjects and the almost photographic framing gave his paintings a very strong figurative presence not devoid of mystery. In the following decade, they tended to occupy the entire production of the artist, who at the same time devoted himself more and more to scenography and writing.

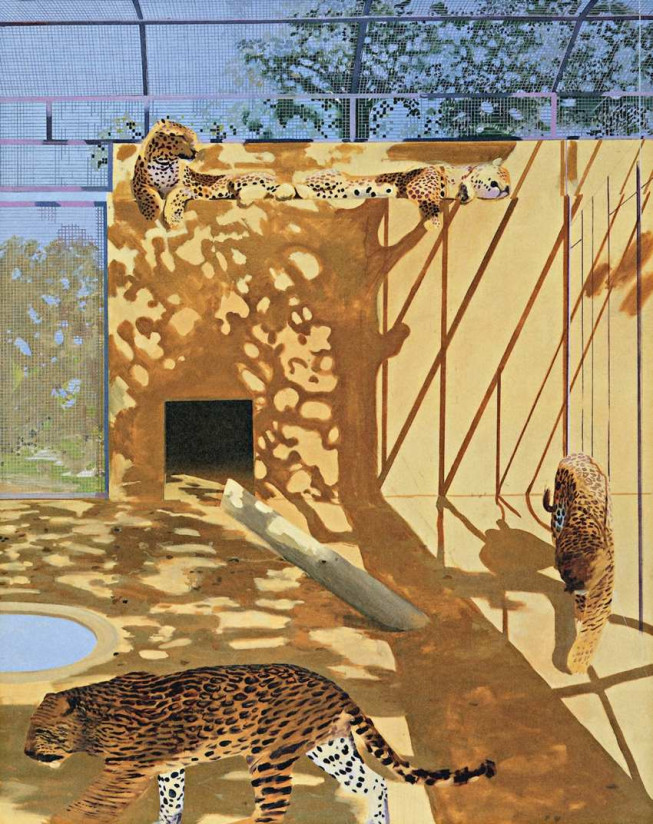

“Rich with some forty pieces chosen from among the most beautiful and emblematic of his extensive production, this exhibition refuses the plethoric demonstration in favor of a sharp, lively and precise route, perfectly arranged so that the views of zoological parks coexist, willingly melancholic, and the African landscapes, ample and dazzling. Tense, this journey is an ode to humility and delicacy, far from the mechanization of gesture and the artificialization of the world. Politics, the animal…” writes Colin Lemoine, who offers us the study of a work by Gilles Aillaud, Panthères, in the January issue of the magazine Connaissances des arts.

Gilles Aillaud, Panthers, 1977, oil on canvas, 250 × 200 cm, National Center for Plastic Arts © Adagp, Paris, 2023/Cnap Photo Galerie Karl Flinker

“If the painter's African stays, notably in Kenya, saw him reconnect with the joy of the outdoors, Aillaud delivers with his Panthers a major reflection on the cloistered solitude of animals and, by his own admission, on “the monstrosity of living in such a place, like humans in a police station.” Going around in circles like lions in a cage, the wild animals of this zoo seem tired or, worse, disillusioned, having nothing else to do than survive, to persist in the living, according to a "stubborn and fascinating reiteration of an insistence of existence to manifest itself,” continues the journalist. “Silence is not peace in this disturbing menagerie scene: the implacable sun creates threatening shadows, the sky is a promise refused by authoritarian fences, the wait in the open air is like torture. Purchased by the French state and deposited at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, this two hundred and fifty by two hundred centimeter canvas has something stifling about it. Five square meters of desolation and torpor, but also of wonder, for the mystery of the beasts and for pure painting. »

After studying philosophy, having been failed at the Ecole Normale Supérieure by Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Gilles Aillaud returned in 1949 to painting, which he had practiced since childhood, without ever ceasing to question the meaning of the world. At the beginning of the 1950s, he created collages of heterogeneous materials which he presented during a first personal exhibition at the Niepce gallery in Paris. In 1959, he exhibited at the Salon de la Jeune Peinture, of which he became president in 1966. In this laboratory of plastic and theoretical experiments, he actively participated in the renewal of the genre, becoming one of the protagonists of Narrative Figuration, after the concept developed by the critic Gérard Gassiot-Talabot.

In 1961, Aillaud met Eduardo Arroyo (1937-2018) with whom he shared similarities in his artistic and political conceptions. In 1964, Aillaud, Arroyo and Antonio Recalcati (born in 1938) created A Passion in the Desert, which they exhibited at the Galerie Saint-Germain in Paris (thanks to an anonymous donation, this narrative fresco joined the collections of the MAM Paris in 2018). Inspired by an eponymous short story by Honoré de Balzac, relating the fantastic loves of a soldier in Bonaparte's army and a panther in the Egyptian desert, it constitutes the first volume of a pictorial manifesto, including Act 2 is Live and Let Die or the Tragic End of Marcel Duchamp (kept at the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid). While the first series boldly claims the right to narrative in painting, the representation of the killing of the inventor of the ready-made arouses a huge scandal. The two works were brought together in 1965 in the founding exhibition organized by Gassiot-Talabot at the Creuze art gallery: Narrative Figuration in Contemporary Art.

Aillaud's political commitment is also expressed in numerous polemical texts and demonstrations which bring together the protagonists of Narrative Figuration and more broadly the members of the Salon de la Jeune Peinture. We found him in 1968 at the Atelier Populaire of the School of Fine Arts, and in particular as part of the “Demonstration of support for the Vietnamese people” organized at the initiative of the committee of the Salon de la jeunesse Peinture. This exhibition, canceled in June 1968 due to the events of May, was presented at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, as part of the ARC (Animation Research Confrontation – contemporary department and multidisciplinary laboratory of the Museum of Modern Art in the City of Paris) from January 17 to February 23, 1969, under the title of “Red Room for Vietnam”. Aillaud notably presents one of the most famous of his political works, Vietnam. The Battle of Rice (1968, private collection), inspired by a press photograph from 1965.

Strictly political paintings, however, remain quite isolated in Aillaud's production, closely linked to the period during which the artist was very involved in the militant activities and collective artistic expressions of the members of the Jeune Peinture. In 1971, the same year as the Daily Realities of Mine Workers, when he was scheduled at the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris for his first personal exhibition, he took down his works as a sign of protest against censorship. and the withdrawal of two works from the neighboring exhibition by the painter Lucien Mathelin by the services of the Prefecture. Among the works taken down was the Rhinoceros from behind, dated 1966.

The painter Francis Biras (1929-2019), the first owner of the Daily Realities of Mine Workers, was close to Gilles Aillaud. He kept them throughout his life as a souvenir of these years of activism and aesthetic upheavals. A painter himself before becoming a scenographer and costume designer, Francis Biras was then secretary of the Salon de la Jeune Peinture. He participated in the collective painting Louis Althusser hesitating to enter the dacha of Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes Miels, where Jacques Lacan, Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes are gathered at the moment when the radio announces that the workers and students have decided to happily abandon their past (1969, private collection). He was also one of the favorite models of several of his Narrative Figuration artist friends. He notably lent his features to the legionnaire of the cycle of A Passion in the Desert. We also know of a marquetry portrait by Eduardo Arroyo: Portrait of the painter Francis Biras disguised as Pierre Loti and his dog Vamos (1973).

While zoo scenes occupy a central place in Gilles Aillaud's production, political or ideological scenes are today among the least known aspects of his work, although they contribute to his recognition on the artistic scene. Parisian from the 1960s. But ultimately, as we now know, all the scenes in all his works of art are political or ideological in nature. “Suggesting that he represented animals, it is our relationship with nature which emerges as its only and true subject,” says today Didier Ottinger, curator of the Center Pompidou exhibition. Thus Gilles Aillaud, although he did not become a philosopher, he always painted with philosophy. And if Socrates thought that politics should be backed by philosophy, Plato went even further, giving a practical mission to the philosopher: that of governing an Ideal City.

Article written by Valibri in Roulotte

Article written by Valibri in Roulotte

Illustrations:

- “Black Bear,” 1982 © DR © ADAGP, Paris, 2023

- Gilles Aillaud, Panthers, 1977, oil on canvas, 250 × 200 cm, National Center for Plastic Arts © Adagp, Paris, 2023/Cnap Photo Galerie Karl Flinker