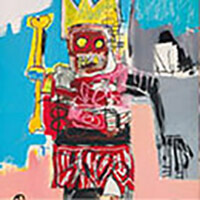

Bright and vibrant Sally Gabori

About the exhibition "Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori" which runs until 6 November at the Fondation Cartier in Paris.

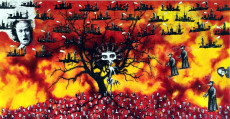

She was a weaver of dillybags, traditional Aboriginal bags woven from plant fibres and used to carry food. She lived from fishing and gathering. She became a painter in her 80s, and today her abstract work is on display in majesty at the Fondation Cartier in Paris. How did Sally Gabori, born around 1924 on an island in northern Australia devastated by a cyclone in 1948, and who died in 2015 on another island in northern Australia where her people were deported, become one of the greatest Australian artists of the last twenty years, and suddenly set the contemporary art market abuzz? It is because exile has taken up residence in her paintings, which are as luminous as they are spectacular. And her style is unlike any other in Aboriginal art.

It is true that Sally Gabori is being discovered in France. "The revelation Sally Gabori" is the title of Beaux Arts Magazine. In Paris, people open their eyes wide in front of her monumental canvases splashing everything with their bright colours. But in reality, she has been a star in Australia for a long time, having quickly become a real darling of the contemporary art scene there. She had only just started painting in 2005, thanks to a painting workshop at a cultural centre where she happened to drop in, when the Queensland Art Gallery devoted her a first exhibition in 2006 in Brisbane, and her paintings took their place on the walls of Australian museums. The breathtaking energy of his gesture was not lost on the professionals. Three years later, she was commissioned by the Supreme Court of Queensland to paint a mural, and in 2013 she exhibited at the Palazzo Bembo as part of the 55th Venice Biennale. A year after her death, in 2016, the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane, the art gallery that had always represented her, organised her first retrospective. Today it is a panorama by Sally Gabori that greets travellers when they land at Brisbane International Airport. And her artworks for sale fetch several thousand dollars.

So what is really surprising is that it will be exhibited in France for the first time in 2022! And even in Europe: by bringing together some thirty of her monumental paintings, the Parisian institution that is the Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain is organising the very first European retrospective of Sally Gabori, this self-taught artist who fascinates as much by her incredible mastery of colours and shapes as by her story. Her story, of course, is that of an old woman living in a retirement home who, on the death of her husband, suddenly metamorphoses into the matriarch of contemporary art, without letting any of her suffering show through in her work, but instead infusing it with joy, light and hope with phenomenal energy. The story of a whole people too.

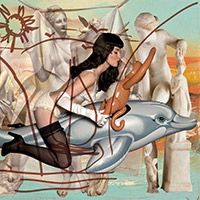

For the woman who was born in Mirdidingki under the sign of the dolphin, as her full name, Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori, indicates, was literally forced, under the pretext of ecological disasters, to leave her native island for the neighbouring island of Mornington in 1948, along with all the other members of the Kaiadilt community, in order for Christian missionaries to undertake... to "civilise" them. Their language as well as their culture and cosmogony were thus promised to die. And the children separated from their parents. "The last coastal people of Aboriginal Australia to come into contact with European settlers, the Kaiadilt thought they would leave for a few weeks. They had to wait four decades to find the original paradise, from which they were separated by barely fifty kilometres," writes Emmanuelle Lequeux in her fascinating article for Beaux Arts Magazine.

They will never give up, the Kaiadilt. They will never give up. Their island, their land, is Mirdidingki, not Mornington. Even though both islands are in the Gulf of Carpentaria, in Queensland. And their exile is one of their own who will eventually bear witness to it all over the world with her paintbrush. She was able to charter a boat to return home with her family after a long struggle to have their territorial and marine rights recognised. The Kaiadilt culture will go down in history with Sally Gabori's painting. And yet painting had never been part of it before. Perhaps this is what made this mother of eight children, and later a loving and devoted grandmother, the extraordinary artist she is today.

The first time she had a brush in her hands, Sally Gabori was able to let all that was in her own memory flow out with the simplicity of pure sincerity. She began to paint compulsively, playing with the primary colours of acrylic paint to return "to the country" through memory and the imagination. "Sally Gabori's artistic initiation was without preconceptions, without the weight of a visual tradition to follow," admires Bruce Johnson McLean, deputy director of the First Nations Art Department at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, the capital of Queensland.

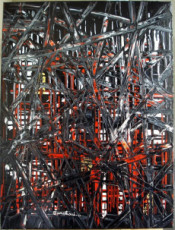

"With no customary painting tradition to draw on, no legacy of signs and symbols that encode meaning, narrate Dreaming Paths or map a cultural landscape, Sally Gabori invents her own style, undermining white preconceptions of what Aboriginal art should look like and mean," enthuses curator Judith Ryan, one of the first to spot her talent as a painter. Sally Gabori's creative outburst has produced two thousand paintings in ten years, encouraged by the contemporary art professionals around her. Her canvases have become larger and larger over time. As a guardian of her "country", she represents Thundi, her father's territory, located near a river running along the dunes, Dibirdibi, the birthplace of her husband, to whom she had a close and intense relationship, or Nyinyilki, one of the places on her native island that was dearest to her heart, a white beach in a lagoon surrounded by casuarinas, where she remembered catching a barramundi and collecting fresh water from Melo amphora shells.

"In each of these immense paintings, which may seem purely abstract, Sally evokes landscapes and portraits," says Juliette Lecorne, curator of the Fondation Cartier exhibition, who travelled several times to Australia to meet the artist's family, to bring the archives out of the wardrobes and return them to the descendants, to translate the songs with which Sally, who did not speak English, liked to accompany her paintings, and to meet her daughters, who in turn embarked on the adventure of painting. However, it is to a visual immersive experience of contemplation that the visitor to the Paris exhibition is invited. "We did not want to essentialise this work by presenting it in an ethnographic light," says the curator. It is indeed the work of a contemporary artist of international renown that we encounter today.