Still life is not dead

About the exhibition "Les Choses" held at the Louvre Museum in Paris until 23 January 2023.

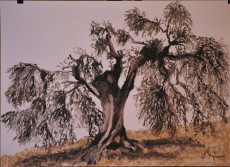

Victor Hugo himself wrote as much in his Contemplations: "For things and being have a great dialogue". Let us open our eyes and ears to perceive this dialogue. For artists were surely the first to take things seriously! And even long before ancient Greece, contrary to what books have always tried to make us believe. You have to see them, the votive axes sculpted 3500 years B.C. on a block of granite on the Breton cairn of Gavrinis, to measure the extent to which man has been honouring the objects of a representation for much longer than that... And without having stopped doing so for a thousand years, as was long believed!

In short, it was time for Laurence Bertrand Dorléac to conduct an investigation to give back to the genre of still life its letters of nobility... and to prove that the representation of things is a far too lively art to keep this generic name invented in the 17th century, only in the specialised field of art history. An art historian herself, the curator of the exhibition at the Louvre prefers the expression "still life" to "thing".

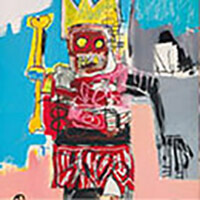

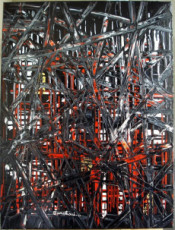

And the title is beautiful. "Les Choses". It makes you think of Georges Perec's novel of the same name, of course. But it also evokes Ponge, Alphant, Montalbetti, Kant, Heudegger, Garcia, Haraway, Harman, Barthes... It opens up so many possibilities! "From the axes of prehistory to Marcel Duchamp's ready-made and Christian Boltanski's collections of objects, via the mosaics of Antiquity and the paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries, the representation of things by artists is always, in fact, a way of speaking about us, our world, our beliefs, our affects," writes Catherine Francblin in the November issue of the contemporary art magazine artpress. The art critic and member of the artpress board of directors appreciates the presence, among the more than one hundred and seventy works of art gathered in this exhibition, of many works by contemporary artists. "And, as a result, all sorts of processes and techniques that are far removed from the traditional vision", thus contributing to "taking Things out of the straitjacket of art history".

Seventy years after the exhibition "Still Life from Antiquity to the Present", presented by Charles Sterling (1901-1991) at the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris, Laurence Bertrand Dorléac is broadening the field of possibilities with this first large-scale event organised since 1952 on this theme. And dealing with the representation of things from prehistory to contemporary art. But the President of the Fondation nationale des sciences politiques, in collaboration with Thibault Boulvain and Dimitri Salmon, also pays tribute to the great art historian who preceded her. It simply proposes a new approach to the subject, entirely renewed. For as Catherine Francblin points out in her article, the genre "has, moreover, an undeniable topicality, given the flood of objects in the consumerist era, but also the many issues that have emerged recently, such as the animal cause, the ecological challenge or the robotization of the world.

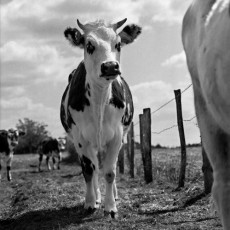

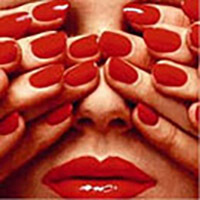

The section of the exhibition devoted to paintings, sculptures and photographs depicting dead animals obviously strikes a particularly sensitive chord in these times of great concern for animal welfare. The sequence is called "The Human Beast" and includes both the motif of the dead animal and the piece of meat. These motifs inspire the artists with very different discourses on humanity. Francisco de Zurbaran's Agnus Dei (1635-1640) or Théodore Géricault's Dead Cat (ca. 1820) show the fragility of existence. But in Nature morte à la tête de mouton (1808-1812), it is the cruelty of wars that Francisco de Goya points out dryly, according to Catherine Francblin, while Rembrandt exalts the greatness of painting with his Bœuf écorché (1655), and Gustave Courbet affirms his political opinions in Trois truites de la Loue (1873). We will also see dead rabbits painted with a strange tenderness by Chardin or the astonishing dead thrush sculpted by Houdon, whose plumage seems incredibly velvety. And what about Cabeza de vaca, the famous cow's head photographed by Andres Serrano at the end of the 1980s, whose accusing look makes the meat-eater so uncomfortable, complicit in the treatment of his species?

All the big names are here, in addition to those already mentioned or to be mentioned later: Matisse, Van Gogh, Foujita, Bonnard, Morandi, Spoerri... are in dialogue with the major classical works of the Louvre and the great international collections, all of which is articulated in fifteen perfectly clear and astonishingly strong sequences that also open up to cinema.

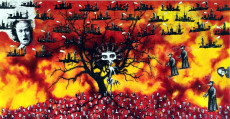

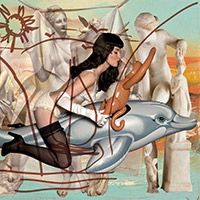

The section that the artpress journalist finds particularly attractive, however, is the one devoted to the very beginning of capitalism, "when artists began to display in their works all the things that accumulate, are exchanged, and are bought. The commodity now occupies all the space in the painting. The peasants disappear into the distance, so enormous are the cabbages of Frans Snyders in his Still Life with Vegetables, dated 1610. The paintings by the Flemish artist Joachim Beuckelaer (c. 1535-c. 1574) converse magnificently with Erro's equally colourful Foodscape (1964), just as Style Life, the famous video of the bowl of fruit filmed in accelerated rotting in 2001 by Sam Taylor-Wood (the contemporary English artist now signing Sam Taylor-Johnson), seems to respond four centuries later to Louise Moillon's Bowl of Cherries, Plums and Melon (1633). Because yes, even in art, women artists used to find it easier to make their mark when it came to dealing with food...

"Through these confrontations, things take on new meanings, but also, thanks to them, the way in which the same objects are taken up again and modified according to the times becomes apparent," observes Catherine Francblin. She illustrates her point with paintings by Marinus van Reymerswaele (ca. 1535), Hieronymus Francken II (ca. 1600) and Esther Ferrer's photographic self-portrait (2002), all of which depict huge quantities of coins. These works of art certainly resonate with each other. "But the former denounces the attitude of a tax collector, the latter the avarice and love of wealth, while the contemporary artist displays her disgust for money in her Europortrait, in which she appears to be vomiting up a cascade of euros during Europe's transition to the single currency," the journalist explains. The viewer thus finds himself here as in a strange art gallery where the works of art for sale would finally denounce... the fact of being for sale.

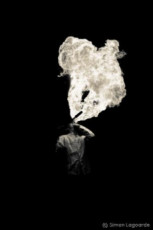

Opening with the music of Pink Floyd and images from the final scene of Antonioni's film Zabriskie Point (1970), which shows the debris of objects pulverised in the air after the explosion of the villa, the Louvre's "Les Choses" exhibition, subtitled "A History of Still Life", closes with an image by Nan Goldin taken during the confinement: a moving, and therefore blurred, photograph of a bouquet of wilted flowers, "which, before us, continue to live beyond their end - and ours". Still holding the visitor at the border between what is alive and what is not...