Women in Surrealism

About the exhibition "Surrealism in the feminine?" presented until 10 September 2023 at the Musée de Montmartre in Paris.

A powerful image has become the emblem of Surrealism, undoubtedly contributing to the Surrealist group's reputation for misogyny. It is the famous photomontage published in the magazine La Révolution surréaliste in 1929 and showing in its centre a small oil on canvas by Magritte depicting a woman, surrounded by the closed-eyed portraits of Aragon, Bunuel, Dali, Ernst, Eluard and Breton among ten other men. "I do not see the (...) hidden in the forest," Magritte wrote on either side of the completely naked nymph surrounded by men in suits and ties. "The meaning of this strange collective portrait is clear: what haunts the unconscious of these artists is THE naked and offered woman," says Isabelle Manca-Kunert in L'Œil of May 2023, which devotes a fascinating investigation to surrealism in the feminine on the occasion of the exhibition of the same name, which questions the subject at the Montmartre Museum in Paris until 10 September.

A provocative and dynamic movement, Surrealism triggered an aesthetic and ethical renewal. But it was not only men who brought this movement and its transgressions to life: many women were major players. The exhibition reveals them and explores their work. "Except that, despite their anti-conformist and revolutionary veneer, the male members of the group remained in fact men of their time and struggled to consider their female colleagues as alter egos," writes Isabelle Manca-Kunert.

By revealing the work of some fifty artists, visual artists, photographers and poets from all over the world, this exhibition invites us to reflect not only on the ambivalent position of women in Surrealism, but also on the capacity of one of the major currents of the twentieth century to integrate the feminine.

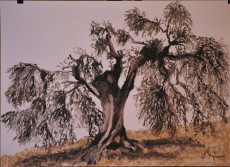

The exhibition aims to present major artists such as Claude Cahun, Toyen, Dora Maar, Lee Miller, Meret Oppenheim and Leonora Carrington, but also to highlight other lesser-known personalities such as Marion Adnams, Ithell Colquhoun, Grace Pailthorpe, Jane Graverol, Suzanne Van Damme, Rita Kernn-Larsenn, Franciska Clausen, Josette Exandier and Yahne Le Toumelin.

Surrealism offered them a framework for expression and creativity that was probably unparalleled in other avant-garde movements. However, it was often by appropriating and extending themes initiated by the movement's 'leaders' that they expressed their freedom.

They also asserted themselves by freeing themselves from what sometimes became a surrealist doxa. Their diverse and complex positions towards Surrealism could be described as "all against" Surrealism.

"Over the years, and thanks to analyses heavily influenced by gender studies, the group's reputation, which had long been praised for its modernity and radicalism, has deteriorated considerably," explains Isabelle Manca-Kunert in her article. "To the point that the group of artists who have most mistreated women, if we rely on Susan Suleiman's studies for example, has been blacklisted as a paragon of misogyny. This sweeping statement of a macho movement that excludes and/or phagocytises women obviously calls for some nuance. If only because exhibitions devoted to these women, who are supposedly absent from the movement, have been multiplying at breakneck speed for twenty years. In the 2022-2023 season alone, the public has been able to discover Toyen at the Mam, Meret Oppenheim at the MoMa, Leonora Carrington at the Mapfre Foundation and, today, the group exhibition at the Musée Montmartre. However, rather than discoveries, these are rediscoveries, since they exhibited within the movement but have since been forgotten by art history.

This relegation to the background is of course true for all artistic movements of the 20th century, not only for Surrealism. The institutions and the art market are therefore constantly being updated, and art galleries are also adapting to the great wind of justice that is now blowing. Works of art for sale by women are being promoted everywhere. It's about time! But in the case of Surrealism, the oversight could also be explained by the art market's lesser interest in the works of art for sale by the second generation of Surrealists. This was a generation in which women artists were making their appearance, whereas at the beginning of the movement women were mainly the muses of the men, like Gala or Simone Breton. Women artists were mainly involved in the movement in the 1930s, producing their mature works in the following decades, i.e. after the war, when abstraction began to take over.

«Today there are many artists who have been completely erased, forgotten, even though they were known in the post-war period," notes Dominique Païni, curator of the exhibition at the Musée Montmartre. "They are major artists, because many of them dared to theorise about surrealism, which was not the case for their colleagues. They were well received by the movement, and by Breton in particular, who supported them a lot and wrote about them. There was clearly a female phenomenon in Surrealism, and it was not so much the movement that stifled it as, subsequently, art historians and the market. To put it plainly: art galleries and museums shunned Breton's and Duchamp's artworks for sale, which made all the other almost non-existent Surrealist works in public collections invisible.

So is surrealism a feminist movement? That is what historian Fabrice Flahutez dares to suggest in his essay, after scrupulously calculating that between 1930 and 1960, it was the movement with the most women in its ranks and the most women's works in its exhibitions! "Although the 1938 Paris International Exhibition had only 5% of its artworks by women, this rose rapidly to 15% in 1947 and then to almost 20% in 1959. Thus, even if the number of women artists remained constant over time (between 10 and 15), the number of their works increased significantly in two decades," writes the art history professor at the University of Saint-Etienne. In short, no other avant-garde movement offered such visibility to women, but of course, everything is relative since men were overrepresented. This is a reflection of the society of the first half of the twentieth century. Ambivalence was also the order of the day, for while the Surrealists did recognise women, they did not shy away from instrumentalising female identity.

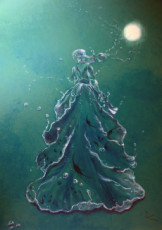

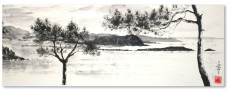

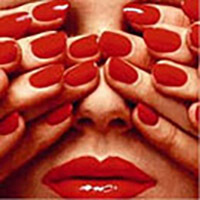

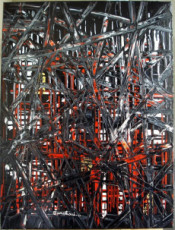

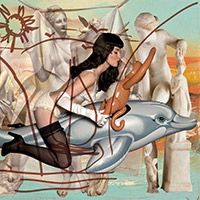

Illustration :

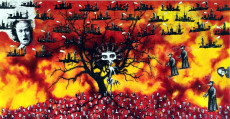

- Poster for the exhibition Surréalisme au féminin? at the Musée de Montmartre (© DR)

- Jane Graverol (1905-1984), The Rite of Spring, 1960, oil on canvas, RAW (Rediscovering Art by Women) (© ADAGP, Paris, 2022, photo © Stéphane Pons)