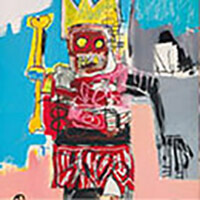

Spotlight on Velazquez's mysterious slave

About the exhibition "Juan de Pareja - Afro-Hispanic Painter" at the Met in New York until 16 July 2023.

His face is familiar, having crossed the centuries thanks to an oil on canvas in the aura of Diego Velazquez (1599-1660), painter to the Spanish crown. But his story is still shrouded in mystery. The painter Juan de Pareja is not just the subject of a famous portrait by Velásquez: he was the Spanish master's slave for twenty years, before making a name for himself as a free man and independent painter. Now, for the first time, his incredible career is the subject of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. This exhibition offers an unprecedented look at the life and artistic achievements of the 17th-century Afro-Hispanic painter Juan de Pareja (circa 1608-1670).

Widely known today as the subject of the iconic portrait painted by Diego Velázquez that caused a sensation in Rome in 1650, and which was acquired by the Met in 1971 for 5.5 million dollars, Pareja was born in Antequera, Spain, to a slave and probably a slave owner. He was enslaved in Velázquez's studio for more than two decades before becoming an artist in his own right. This presentation is the first to attempt to tell his story, but also to examine the ways in which slave labour and a multi-racial society are inextricably linked to the art and material culture of Spain's 'Golden Age'. For all too often they are forgotten, the talented slaves employed in painters' studios, endlessly reproducing works of art to be sold for the benefit of their masters!

Representations of the black and Morisco populations (Muslims forcibly converted to Catholicism in the sixteenth century) of Spain in the works of Francisco de Zurbarán, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo and Velázquez join works that trace the ubiquity of enslaved labour across media from sculpture to money. The portrait of the Met, executed by Velázquez in Rome in 1650, is contextualised by his other portraits from this period and the original document by which Pareja was freed on his return to Madrid. The exhibition concludes with the first-ever gathering of rarely seen paintings by Pareja, some of enormous scale, which engage with the canons of Western art while reverberating throughout the African diaspora.

Arturo Schomburg (1874-1938), collector and Harlem Renaissance scholar, played a key role in the recovery of Pareja's work and serves as a thread linking seventeenth-century Spain to twentieth-century New York, providing a lens through which to view the many stories that have been written about Pareja. For art historians, Juan de Pareja has long been relegated to the role of a painter who remained in the shadow of his "master", whom he sought to imitate without ever equalling, "while a host of myths and anecdotes have written the novel of the former slave with a singular destiny", points out Daphné Bétard in her article for the June 2023 issue of Beaux Arts Magazine. "The Met's current retrospective of Juan de Pareja is just the beginning of a story that has yet to be written," say the exhibition's curators David Pullins, curator at the Met, and Vanessa K. Valdés, writer and professor at City College, New York.

"Even if the paintings by the genius of the Spanish Golden Age seem to speak of otherness today, with his way of treating a slave and a pope, a princess and a beggar in the same way, he practised slavery, as did his entire family," points out the journalist from Beaux Arts Magazine. Indeed, as early as the 1630s, Pareja's name was mentioned in Velazquez's Madrid studio. And the man didn't just grind the pigments or prepare the canvases, like most other painters' slaves. He worked with the master's assistants on copying work, which was much more rewarding. He was on a par with Juan Bautista Martinez del Mazo, Velazquez's own son-in-law. Of course, the king's painter had to respond to numerous commissions for paintings, and copying was commonplace at the time. Copying in the studio was a profession in its own right. As if today a contemporary artist's original work of art were displayed in an art gallery or in an art market catalogue, and collectors or ordinary art lovers could buy a reproduction of it as they wished, painted as a carbon copy by other contemporary artists who remain anonymous.

Nevertheless, Pareja's role was strangely so important to Velazquez that it was he, the slave, whom the master took on his trip to Italy, financed by the Spanish crown to acquire works of art for sale and plaster casts of ancient sculptures. "For Pareja, it was a kind of grand initiation tour that began in Genoa in January 1649 and continued through Milan, Modena, Bologna, Florence and Parma before ending in Rome in May," writes Daphné Bétard. "Then Velazquez painted the famous portrait that dazzled the whole city and highlighted the anonymous assistant who had also taken up the cause of painting, a discipline that Velazquez wanted to be recognised as equal to the noblest arts. Was this the ultimate reason why he finally granted him his freedom? What was the relationship between the two men? Why did he, Pareja, choose him for the trip to Italy? The legal and administrative documents put an end to any speculation. But on his return to Madrid, after the four years he still owed Velázquez as a slave, Pareja finally made the transition from studio copyist to independent artist."

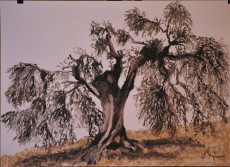

And contrary to what some art-historical malcontents claim, Juan de Pareja did not paint a "sub-Velazquez". He was part of the contemporary art movement of his time, the Madrid School led by court painters Francisco Rizi, Claudio Coello and Juan Carreno de Miranda. "A sort of new version of Spanish Baroque, with exuberant, rhythmic compositions and a luminous palette, reinterpreting the Venetian painting of Titian and Veronese, with a little Flemish touch à la Rubens", describes the Beaux Arts Magazine journalist. "Pareja pays particular attention to the textures of the fabrics, the contrasts of the expressions and the movements of the bodies. He pays particular attention to the landscapes in the backgrounds, which he skilfully elaborates. A painting like The Flight into Egypt (1658) is a far cry from the sobriety of Velazquez, with its trees tormented by the wind, white reflections like flashes of light, and pink angels and cherubs soaring through the air!

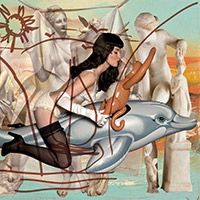

Illustration: The Calling of Saint Matthew

Juan de Pareja (Spanish, Antequera 1606-1670 Madrid)