The icon, an open window on the elusive

About the "Icons" exhibition, on view until 26 November 2023 at the Punta della Dogona in Venice.

The incised canvas by Lucio Fontana (1899-1968) opens up a new dimension right at the start of the Icons exhibition, which is structured around works from the Pinault Collection and invites visitors to reflect on the theme of the icon and the status of the image. It can be seen until 26 November 2023 at the Punta della Dogona in Venice. This prestigious collection of contemporary art is not just about boosting the market value of the artists whose works the billionaire collector buys for sale. Nor does it miraculously replenish the coffers of the art galleries that represent these artists. It is also, of course, a veritable goldmine for exhibitions on all sorts of themes, with works of art seen and interpreted differently each time.

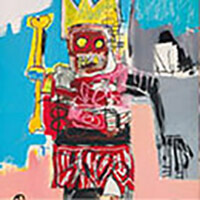

"This singular subject, justified by Venice's link with the Byzantine East, provides an opportunity to draw attention to works that have rarely or never been shown before, most of them pleasant surprises," writes Catherine Francblin in her article for Artpress, the June issue of the contemporary art magazine. "A good number of the participants (James Lee Byars, David Hammons, Danh Vo, Rudolf Stingel...) are familiar with events organised in Paris or Venice in the past but, thanks to the question of the icon, it doesn't seem to have been difficult to widen the circle of the privileged while conforming to a sort of home-grown state of mind that Tadao Ando's building helps to reinforce".

"It is a given that the very essence of the icon shines through in Kandinsky's and Malevich's transition to abstraction, as they experienced spaces transfigured by the presence of icons, whether churches, chapels or isbas with painted walls, as Kandinsky discovered them on his trip to the province of Vologda in 1889," writes Emma Lavigne, Managing Director of the Pinault Collection and curator of the exhibition. "The immersion in colour associated with the radiance of icons, glowing in the light of candles in the sacred eastern corner of houses, was a decisive step in his quest for the invisible, which he called 'spiritual' in Du Spirituel dans l'art in 1912. At the "Last Futurist Exhibition 0.10" in Petrograd in 1915, Malevich transposed the beautiful red corner where the icons were displayed into the space so that it could become the setting for the Black Square on a White Background, which he considered to be the "icon of our time".Inspired by the icon painters, who did not use colours or forms faithful to reality, as well as by the sound and rhythmic poetry of the poet Khlebnikov, Malevich invented autonomous plastic elements that freed themselves from the visible world and mimesis. In his manifesto Suprematism: The Objectless World or Eternal Rest, 1919-1922, he sought to explore the ways in which the world existed beyond the visible. As Bruno Duborgel analysed in Malévitch, la question de l'icône, the challenge for him was to make the relationship between the visible and the invisible visible, to reveal the nature of the image not only in its visibility but above all in its link to the invisible.

Among the pleasant surprises mentioned in her article, the Artpress journalist mentions the installation by Lygia Pape (1929-2004), one of the most important figures of the Brazilian artistic avant-garde, made up of golden threads stretched in the dark and provoking an emotion of a religious nature. "The icon gives life to the invisible", writes Marie-Josée Mondzain, a philosopher specialising in art and images, in the exhibition catalogue published by Marsilio, going on to highlight the musicality of the "deceptively austere" work of Agnes Martin (1912-2004). While it is true that the American artist has often been associated with the Minimalist movement, because of the sobriety and regularity of her forms, she herself considered herself closer to the Abstract Expressionists, her contemporaries. Considering music to be one of the highest forms of art, the iconic painter turned her works into veritable scores to be deciphered.

"The challenge facing any thematic exhibition is to make the reasons behind the choice of works and artists intelligible or sensitive. Icônes is no exception, offering a range of experiences from the contemplation of Robert Ryman's ultimate works of absolute simplicity, brought together like those of Roman Opałka in a kind of sanctuary, to the visual and aural shock of Arthur Jafa's videos," says Bruno Racine, co-curator of the exhibition. In the catalogue, he "distinguishes the idol from the icon, before focusing on a few emblematic works, such as Maurizio Cattelan's La Nona Ora (1999) and Kimsooja's filmed performance, which is both an experience of 'self-affirmation' and of 'belonging to humanity'", notes Catherine Francblin in Artpress.

"While the Byzantine painters whose icons scandalised the iconoclasts had no intention of offending anyone, Cattelan was perfectly aware that La Nona Ora would spark off controversy," says Bruno Racine. "But what exactly do we see in Cattelan's work, beyond or in spite of his mimetic realism? Curiously, the Pope's face is not distorted by pain, as you might expect, even though it should be unbearable. His expression is grave, and seems essentially collected, perhaps surprised by a statistically improbable accident; and his body, instead of being reduced to rubble by the impact of a stone of this size hurled at full speed through space, remains intact. What's more, John Paul II, firmly clinging to the cross, seems to be making an effort to get up. It's hard not to think here of the scenes of torture so often depicted in Italian churches, where the martyrs, indifferent to suffering, emerge unharmed from the flames or boiling oil and defy the repeated efforts of their executioners. Even if the controversy has died down, La Nona Ora remains, in 2023 as it was in 1999, what the artist intended it to be: a work that is disturbing, even shocking at first sight, but which, in his own words and with reference to the Passion of Christ, is "a spiritual work that speaks of suffering".

The decision to bring the artists together in small groups of two or three sheds further light on the exhibition. For example, a rotunda designed by Roman Opalka to house his paintings of numbers is found here between a group of studies by Josef Albers for Homages to the Square, and a sixteen-metre-wide painting on tracing paper by Michel Parmentier. Robert Ryman's small square paintings are brought together in a space conducive to meditation, while the nocturnal images in Philippe Parreno's film devoted to Goya's black paintings invite us to take a journey among ghosts. As Catherine Francblin concludes, "Such is the icon: a window onto an elusive elsewhere, between light and shadow, admiration and terror.

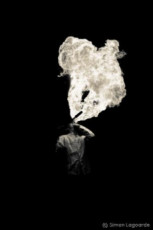

Illustration: David Hammons, Black Mohair Spirit, 1971 Pinault Collection © David Hammons