Medusa in all tenses

About the exhibition "Under the gaze of Medusa. From Ancient Greece to Digital Art", on show at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Caen until 17 September.

Once you've managed to find the entrance to the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Caen, an astonishing architectural masterpiece of contemporary art nestled in the midst of the labyrinthine renovation of a medieval castle, which happens to be the former home of William the Conqueror... the hardest part is over. The exhibition devoted to the mythical figure of Medusa is brilliant in every way! With precise labels, neither too much nor too little, it offers a very interesting tour to be discovered until September 17. And even if you thought you already knew quite a lot about this creature with the serpentine hair and petrifying gaze, you'll be delighted and amazed to discover plenty more as you wander among the works of art, "Under the gaze of Medusa. From Ancient Greece to the Digital Arts". The title of this beautiful and inspiring exhibition.

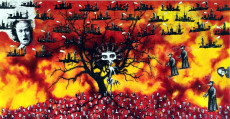

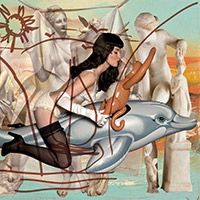

In the end, it was never properly explained to us that, in one version of the myth, Medusa was struck with this terrible curse by the goddess Athena, who wanted to punish the young Gorgon... for having been raped! It's easy to understand why this figure, often associated with a negative image of the 'femme fatale', has now become a powerful feminist symbol... In fact, we leave the exhibition with a smile on our faces and the feeling that art can do justice, after admiring the large bronze sculpture by contemporary artist Luciano Garbati, dated 2023, which shows Medusa holding Perseus's head, rather than the other way round!

A key figure in Greek mythology, Medusa has exerted her power of fascination on many generations of artists, who have contributed to the creation of an incredibly rich repertoire of images. Commonly recognised by her hair swarming with snakes and her wide-set eyes, the figure of Medusa has been constantly renewed throughout the ages. The exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Caen is devoted to the evolution of these representations, from the earliest iconographic sources of Antiquity to the most recent artistic productions.3, and choosing to depict Medusa holding Perseus' head, rather than the other way round!

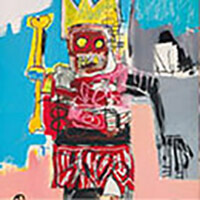

The exhibition brings together sixty-five works by the greatest artists, held in French and international collections. From the ancient Greek sculptor Crésilas to today's artists: Benvenuto Cellini, Sandro Botticelli, Pierre Paul Rubens, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Adèle d'Affry, Jean-Marc Nattier, Theodor van Thulden, Maxmilián Pirner, Franz von Stuck, Edward Burne-Jones, Antoine Bourdelle, Auguste Rodin, Alberto Giacometti, Luciano Garbati, Laetitia Ky, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster... The exhibition spans the fields of painting, sculpture, drawing, printmaking, photography, the decorative arts, cinema and video games. These multiple perspectives provide a rich, paradoxical and up-to-date vision of this fascinating figure, several thousand years old.

In the summer issue of the art magazine L'Oeil, Isabelle Manca-Kunert offers six keys to understanding "why Medusa inspires so many artists". First of all, the journalist points out that the motif is both terrifying and protective. "Medusa is one of the most famous myths of Antiquity, a character so well known that her name gave rise to an adjective that is still used today and which means to be stunned," she begins. "For the Greeks, the Gorgon Medusa ruled over the gates of Hades, the frontier that symbolically separated the world of the dead from that of the living. She was endowed with a terrifying power, since she could petrify anyone who looked her in the face. This frightful creature is instantly recognisable as a severed head whose hair is made up of a myriad of furious snakes. Paradoxically, despite its horrific nature, this image was also invested with an apotropaic dimension, as the ancients believed that its representation had the ability to ward off bad luck. That's why this frightful, grotesque visage was painted and sculpted on all sorts of surfaces: from temple pediments to shields, not forgetting domestic objects such as crockery.

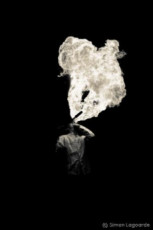

As a second "key to understanding", Isabelle Manca-Kunert explains that unlike the ancient artists who most often immortalised Medusa in the guise of a monster, the artists of the modern period "exploited the ambivalence and malefic beauty of the character". Another reason why the Gorgon was so highly praised was that "they saw in her an allegory of the gaze and the image, and thus a mise en abîme of the status of art. This metaphor is all the more convincing in the case of sculptors, who literally have the ability to petrify their models.

As the third key to explaining the plethora of Medusa representations over time, the L'Oeil journalist suggests "the opportunity to glorify a real hero". For "the fate of the creature is inextricably linked to the adventure of Perseus, the ancient hero par excellence. In order to save his mother, who was threatened by the tyrant Polydectes, the demigod, son of Zeus and Danae, promised the despot that he would bring back Medusa's head. Protected by two major deities - Athena and Hermes - who provide him with such precious accessories as a helmet of invisibility and winged sandals, he courageously accomplishes his feat. From the Renaissance onwards, artists made the most of this positive character, who embodied the struggle between good and evil, and whose legend is full of scenes that make for elaborate compositions".

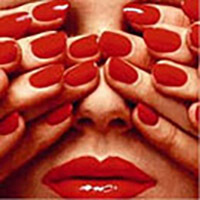

"The fascinating beauty of horror" is the fourth key offered by Isabelle Manca-Kunert. "The fragmentary aesthetics of this evil body, with its wide-open eyes, its face deformed by the pain of decapitation and its hair made up of snarling snakes, is as astonishing as it is repulsive", writes the journalist. Proof of this is the sublime (in the literal sense of the word) painting by Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snyders, featured in the exhibition: Beheaded Medusa, dating from 1617-1618. A work of art purchased by the Vienna Museum of Art and History. A work of art for sale as a postcard in the museum shop... so terrifying that you wonder who you'd dare send it to!

The fifth argument put forward by the journalist to explain the iconographic and sculptural success of Medusa is that she is "a good pretext for a sexy nude". Obviously, this is not about Medusa's horrible head washed up at Perseus' feet, which suddenly becomes sexy, but about the beautiful Andromeda, delivered by the hero who discovers her chained naked to a rock, ready to be devoured by a monster...

And finally, the sixth and last key to this section: Medusa is said to be "the paragon of the femme fatale". In the eyes of the Symbolists, "the monster embodied feminine omnipotence, hypnotising man and leading him inexorably to his ruin". The Gorgon thus became anything but a hideous monster. The link between the Gorgon and sexuality is one that psychoanalysis will continue to develop. And given its current appropriation by feminists and contemporary art, we can only conclude that, over the centuries, the myth of Medusa has never ceased to be updated...

Illustration: Luciano Garbati, - Medusa holding the head of Perseus. The statue of Medusa holding the head of Perseus on display in front of the courthouse in New York City.