Monet in the light of the South

About the "Monet en pleine lumière" exhibition, on view until 3 September at the Grimaldi Forum in Monaco.

Marie Zawisza's report in the summer edition of L'Oeil magazine gives us a glimpse of the magic of the "Monet en pleine lumière" exhibition, which opened at the Grimaldi Forum in Monaco on 8 July to mark the 140th anniversary of the Impressionist master's first visit to Monte Carlo and the Riviera. The journalist follows in Monet's footsteps to help us understand what he sought, and found, in the light of the South. Until 3 September, visitors to Monaco will be able to enjoy a delightful sunbath, play hooky with the famous painter and approach his work from a new angle.

"I ask you not to speak of this trip to anyone", wrote Claude Monet (1840-1926) on 12 January 1884 to his invaluable Parisian art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who was providing financial support for the Giverny painter, who then had eight children to support and was stubbornly looking for takers for all his works of art for sale... However, money was desperately needed in this blended family, which had been viewed negatively since the death of Camille Monet and the departure of Ernest Hoschedé, leaving Claude and Alice to lead an illegitimate married life. Placing all his hopes and his commercial strategy on a renewal of the painter's subjects, the art dealer did not risk revealing what had just been entrusted to him: Claude Monet wanted to work alone in the light and on the motifs of the South that he had just discovered with Renoir. "As pleasant as it was for me to make the trip as a tourist with Renoir, it would be just as embarrassing for me to do it as a couple in order to work. I have always worked better in solitude and from my impressions alone. So keep it a secret until further notice. Renoir, knowing I was about to leave, would no doubt want to come with me, and that would be just as bad for both of us.

It's too good to be true! At last, new works of art for sale! At last, the painter of storms and mists, of the atmospheric effects of the Normandy coast and the Paris region, was going to "bring back a whole series of new things", as he wrote to Paul Durand-Ruel. Durand-Ruel readily agreed to finance the trip. And in fact, Monet returned three months later to his studio in Giverny to put the finishing touches to... Forty-six new paintings for sale! The number of works of art he usually produced in a year. "The man who liked to paint easel against easel, with Renoir and Sisley, thus put a definitive end to companion painting," observes Marianne Matthieu, curator of the Monegasque exhibition. "From that date onwards, his development was markedly different from that of his peers," she notes.

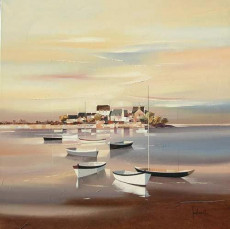

In Monaco, at the Grimaldi Forum, the light is above all that of the Riviera, which Claude Monet visited in 1883-1884 and again in 1888. Twenty-three canvases painted in Monaco, Bordighera, Sasso, Dolceacqua, Cap Martin and Antibes form the heart of the exhibition and the starting point for the curatorial approach. The first aim is to reveal these uniquely toned paintings, their "palette of diamonds and gems", and highlight their singularity in Monet's work.

The 1880s marked a major turning point in Monet's life and work. He moved to Giverny and distanced himself from the Impressionist group. He no longer painted only the Paris region and Normandy. He now ventured from region to region, seeking out new motifs. His stay in Monte Carlo in December 1883 was the starting point, and heralded the turning point of the countryside. It was in the same South of France, five years later, that Monet initiated another change, that of the series: painting the same subject as many times as the atmospheric effects dictated.

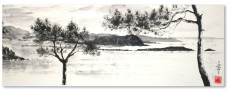

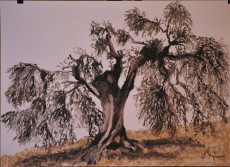

The trips to the Midi heralded two fundamental elements in Monet's work: the principle of the countryside and that of the series. There was therefore a before and an after to Monet on the Riviera. Monet's evolution corresponded to the evolution of his point of view. In the first part of his life, he adopted a traditional point of view but showed little interest in the motif. His ambition was to paint atmosphere. He wanted to paint what lay between him and the subject. The subject is of little importance, what matters is when he paints it.

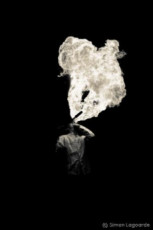

To share this way of looking at things and make it one of the focal points of the visit, an entire room is devoted to it at the opening of the exhibition. In this way, everyone is invited to see as Monet did. To look for the "when" rather than the "what", to read the moment before reading the motif. This is followed, in Rooms 2 and 4, by landscapes painted from Honfleur to Giverny, via the Riviera, presented in pairs when they deal with the same motif, inviting visitors to exercise their gaze and read, like Monet, the effect rather than the subject. At the turn of the century, Monet went further. He no longer painted landscapes in the classical sense of the term. The horizon disappeared. Monet depicted the mirror of water, the water lily pond he had created in the garden at Giverny. This painting, which excludes the representation of the horizon, the sky and the earth, awakens "the idea of the infinite". Monet painted space and light.

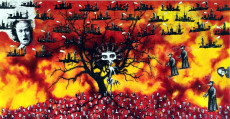

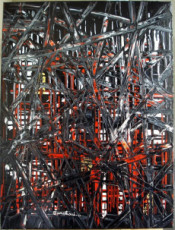

A second room of points of view (room 5) explains and illustrates this radical development, which took Monet's work well beyond Impressionism and right up to the threshold of modern art. This is followed by his most innovative paintings, from the emblematic waterscape series (room 6) and the garden series (room 7): 38 paintings of water lilies and other flowers. At the heart of Room 7 - "Between War and Peace, the Great Decorations" - is an innovative, well-documented and sensitive presentation of the context in which the monumental panels that occupied Monet from 1914 to 1926 were created, and their significance. All of these elements place Monet in the spotlight, inviting us to appreciate his work in a new light. Finally, Room 8 brings the tour to a close, showing the work of an artist in the early days of abstraction.