A little tour of “whistlerism”

About the exhibition “James Abbott McNeill Whistler: The Butterfly Effect”, on view at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rouen until September 22.

To mark the 150th anniversary of the birth of Impressionism, the Rouen Museum of Fine Arts is offering visitors this summer the chance to immerse themselves in an “artistic phenomenon” called “Whistlerism”. But who is this artist whose artistic approach and philosophy of art are described as a “phenomenon” to the point of giving his name to a pictorial movement? Why is he still relatively unknown in France, when in his time he fascinated Proust, Huysmans and Oscar Wilde? When he was even the equal of Cézanne as a leader of 20th century painting? What is so special about James Abbott McNeill Whistler, an American painter, draftsman and engraver born in 1834 in Massachusetts, who died in London in 1903, and who stayed in Normandy several times, notably with Gustave Courbet (who was his friend before stealing his wife)?

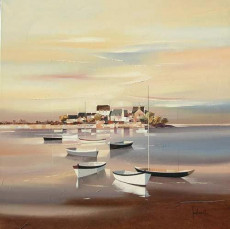

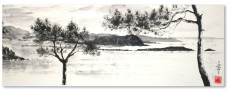

First, he is a fervent defender of the idea that art should be appreciated for its intrinsic beauty and not for its moral, narrative or didactic content. This notion is encapsulated in the "Art for Art's Sake" movement. Then, influenced by Japanese art, Whistler integrated elements of composition, simplification of forms and the use of empty space, emphasizing a minimalist and refined aesthetic. He is also recognized for his mastery of subtle colors and harmonious tones, having often used restricted palettes to create atmospheric and emotional effects. His Nocturnes, for example, are famous for their shades of blue and gray that evoke foggy night scenes with very fine material, unlike those of Turner. Finally, Whistler compared his paintings to musical compositions, using terms like Symphony, Nocturne and Arrangement to title his works. This comparison underlines the importance he gave to composition and visual harmony, similar to those of a piece of music.

The exhibition "James Abbott McNeill Whistler: The Butterfly Effect", which is being held at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen until September 22, is therefore designed to be an immersive sensory experience. Visitors can not only admire Whistler's works, but also enjoy the music, textiles and fragrances that complement their contemplation. A multi-sensory approach to works of art, which engages not only sight, but also touch and hearing, to offer a more enriching and emotional experience. Children are not left out, with a guided tour by the characters of the comic strip "Ariol" created by Emmanuel Guibert and Marc Boutavant, in order to make Whistler's art accessible to young visitors, to foster intergenerational links and to make the exhibition fun and educational.

The works of art exhibited in this exhibition, even if we can regret the few American loans that would have avoided drowning Whistler's paintings a little among those of his emulators, include landscapes, portraits and night scenes, demonstrating Whistler's qualities as a colorist. His subtle use of colors and his talent for capturing ephemeral atmospheres are indeed well highlighted, notably through his famous nocturnes and his diurnal views of London and Venice. But as Sophie Flouquet reminds us in her article for the summer issue of Beaux Arts Magazine, "the American painter was adored in his time, before being erased in France by a somewhat chauvinistic critic who instead focused on the Impressionists, his contemporaries." Hence the event that this exhibition constitutes in the form of "a look back at an uncompromising career and the artist's nebula," since since 1995, no French museum had devoted an exhibition to the leader that was James Abbott McNeill Whistler!

It must be said that if we sum up his work in a few majestic, rather dark portraits, with rigorously controlled harmonies and perfectly smooth pictorial material... we wonder what has lent itself so much to ecstasy. What work of art better embodies austerity than the famous portrait of his mother, devilishly hieratic and soberly entitled Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1? Nevertheless, it has never ceased to be revisited, even pastiched, by artists from all over the world. "It was above all at the center of an incredible mobilization of artists, poets and art critics in order to be purchased by the French State - in 1891, twenty years after its creation," recalls the journalist from Beaux Arts Magazine. "Which was done, which is why the large painting now hangs on the walls of the Musée d'Orsay, where Americans rush to see this heritage icon that they would dream of seeing hanging in their homes. »

Given the fascination that the artist exerted, the art critic Camille Mauclair spoke at the time of "a movement of mysterious sensitivity propagated around Mr. Whistler". In his Hommage à Delacroix, the painter Henri Fantin-Latour had not hesitated in 1864 to place Whistler at the center of the composition which notably featured Baudelaire and Manet. He has him holding a bouquet of flowers, as if to better designate him as an obvious intermediary between the champion of romanticism and his peers. When at the Salon of 1863 two works of art for sale caused a scandal, it was neither more nor less the famous Déjeuner sur l'herbe by Manet, that much is known, but also Symphony in White No. 1: The Young Girl in White by Whistler. And that much less is known. However, the painting had already been rejected the previous year by the Royal Academy in London, suspected of representing a young girl who had lost her virginity… and therefore deemed inappropriate.

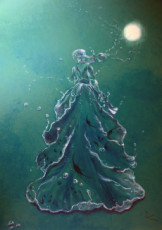

Was Whistler a revolutionary? Neither a naturalist nor an impressionist, he nevertheless flatly refused Degas’ invitation to exhibit in 1874 with the young rebels of contemporary art at the time. He preferred to sell his works of art at the Salon, which then ruled the entire art market in Paris. But he never stopped kicking the anthill of academicism. Let’s just say that Whistler is difficult to pin down. Between the austere portrait of his mother and the marvelous painting where his partner Joanna poses in a total Japanese look, he sowed his butterflies with outstretched wings on some of these paintings, and a breath of fresh air on the entire history of art.

When the eminent English art critic John Ruskin published a text in 1878 vilifying his Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, he kicked up a slander. He directly filed a libel suit against this John Ruskin, author of the now famous phrase: "I did not expect to hear a scoundrel ask for two hundred guineas to throw a pot of paint in the face of the public." And he won! Of course, Whistler was ruined after this very costly legal joust. But his reputation was so enhanced that it was at this time that the astonishing term "Whistlerism" emerged. An aura more than a school.

Article written by Valibri en Roulotte

Article written by Valibri en Roulotte

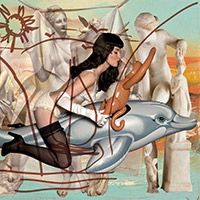

Illustration: James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl, 1864. Oil on canvas - © Tate Britain