Contemporary art market or commercial art?

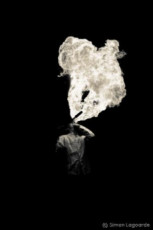

About the exhibition “BeauBadUgly – The Other History of Painting”, visible until March 9, 2025 at the MIAM (International Museum of Modest Arts), in Sète.

“The flirtation with a kitsch, popular and even vulgar aesthetic has tempted representatives of almost all movements of modern art and all trends in contemporary art.” It is not me who says it, but Catherine Millet herself, who writes it in the summer issue of the magazine Artpress of which she is the editor. On the occasion of the exhibition “BeauBadUgly – The Other History of Painting”, visible until March 9, 2025 at the Musée international des arts modests, in Sète (aka Hervé Di Rosa’s MIAM), the prestigious reference magazine of contemporary art is devoting a fascinating file to the titillating question: according to what criteria do we judge works of art as being commercial and in bad taste… rather than works of contemporary art? When I tell you that it’s fascinating! Given the scope of the subject, the famous art critic is not tackling it alone. Four other “experts” have been commissioned to give their opinion on the famous question. So I may tell you another day about the points of view of Paul Ardenne, Annabelle Gugnon, Romain Mathieu and Thomas Schlesser, but, with all due respect, I will start with the chef.

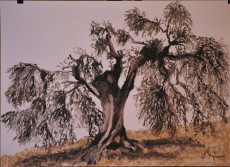

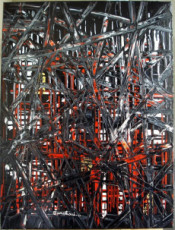

First, a little background. The exhibition is presented in two parts: in the "historical" part, we find the "stars" of so-called commercial painting, such as Vladimir Tretchikoff (yes, you know, that hyper-colorful portrait of a Chinese woman that appears in a David Bowie video as well as in an Alfred Hitchcock film, and which made this highly controversial self-taught Russian one of the richest painters in the world), but also Bernard Buffet (yes, his clowns having become too popular too quickly, he plays in this category), or Félix Labisse and his blue women, in short, all those whose works of art for sale have precisely "sold too well to be honest".

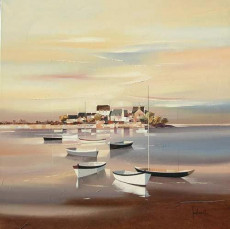

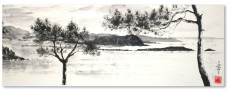

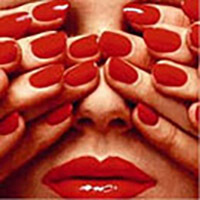

This panorama of commercial, media and popular painting is staged by Hervé Di Rosa and Jean-Baptiste Carobolante, the author of a study that served as a starting point for this exhibition, and focuses on the different trajectories that this pictorial field has taken in the 20th century: from the idealization of the female body to the tourist landscape, through the media coverage of painters and the birth of a new popular artistic public. Each time, the paintings presented are as much a reminiscence for the public as a radical discovery.

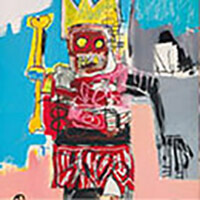

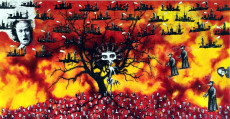

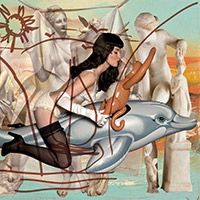

In the second part, which can be described as "contemporary", we find for example John Currin, Richard Fauguet, Gérard Gasiorowski, Pierre et Gilles, Ida Tursic & Wilfried Mille, and Nina Childress who is also the co-curator of this part with Colette Barbier, long-time director of the Pernod Ricard Foundation. What amuses me is that according to Catherine Millet, it is these last names that should be more familiar to us than the others... So be it. In any case, this selection of contemporary works allows us to show the importance of "merchant painting" in the contemporary artistic imagination. And shows to what extent the merchant world has become an essential iconographic reference field for understanding the roots of contemporary creation.

So to find your way around, if you sometimes have doubts, it's simple: the historical part is on the ground floor of the MIAM, the contemporary part upstairs. And the three hundred "crusts" painted with a knife, by the very conceptual Gabriele Di Matteo, all the same but all different, make the link between the two, between history and the present. In particular, the exhibition presents many variations on the legacy of the famous Parisian figure of "Petit Poulbot".

But let’s get back to Catherine Millet’s analysis for Artpress, who considers that BeauBadUgly is not only one of MIAM’s most audacious projects, but that it is even more relevant than High and Low, the major exhibition held at MoMA in New York during the winter of 1990-91, drawing up a vast panorama of modernity borrowed from popular arts. Just that! “Of course, MIAM does not have the means of MoMA,” she nevertheless acknowledges, “but its impertinent project is also more relevant: to confront works of contemporary art that use forms and themes specific to popular imagery with those of artists who have created very popular works, but without registering in the field of contemporary art. That is to say, comparing original works with other original works that often resemble each other, but which are not distributed within the same market, the contemporary art market for some, the Place du Tertre or department stores for others. "Yes indeed: selling your works of art in an art gallery or in a supermarket, that's the difference. You have to choose (if you can).

The reader that I am obviously can't help but think that it works exactly the same in literature! If you read Marc Lévy, Agnès Ledig or Guillaume Musso, I warn you, you will never play in the same league as those who read illustrious unknowns and who will always look down on you. The same if you are the writer. You won't want to eat that bread. Still, if you want to make money by publishing novels, you will dream of selling as many as the popular authors I just mentioned (there are others). Because that is the problem at heart: how can you live (well) from your art if it is not commercial? Catherine Millet even suggests that “contemporary artists” are not always above the commercial considerations attributed to “merchant artists”… In her own Musée du Mauvais Goût, the art critic does not hesitate to hang Francis Picabia’s Nudes, Andy Warhol’s Dick Tracy, Superman and Popeye, Peter Arno’s comics revisited by David Salle, Robert Zakanitch’s all-over florals, Alain Séchas’s Chats et les Papas, Barnett Newman’s zips transformed by Philip Taaffe, and even Hervé Di Rosa’s own cyclops…

“Conversely, the general evolution of taste induced by modern art has had an influence on merchant painting,” she believes. “This is evidenced by the chromatic and artistic freedom that André Brasilier and Vladimir Tretchikoff allow themselves.” The swan wings forming the celestial vault of Stephen Pearson’s Wings of Love (1972) are a sentimental degeneration of the dream space and double images of Salvador Dali. However, there is a threshold of ugliness or a type of ugliness that commercial painting does not risk: if it admits the monstrous eyes painted by Margaret Keane, I doubt that the squinting eyes of Stéphane Zaech or the “smeared” ones of Nina Childress will find success there. There is a limit to commercial art, it is irony.” I love it. As I love the new question with which Catherine Millet finally answers the first: “What would happen in the minds of the public(s) if the hanging decision had mixed all the works?” I think we would have some surprises.

Article written by Valibri en Roulotte

Article written by Valibri en Roulotte