Read for you in ART PRESS

Mega-galleries and mega galleys

It is obvious that the world of galleries in France underwent a real revolution during the 2000s. Where are they today? To take stock, Art Press met the economist Nathalie Moureau on the occasion of the release of the book Histoire des galeries d'art en France du 19e au 21e siècle in which she wrote a text entitled Le temps des galeristes which covers the period from 1980 to today. For her, this interval includes two very distinct periods. The first begins with the creation of the regional funds for contemporary art (Frac) following the arrival of the left in power in 1981. This creation was part of the ambient void of a market without major private collectors unlike our neighbors like Germany and Italy with notably and respectively Peter Ludwig and the Panza family. Criticized for producing "official" artists, this institutional system has nonetheless worked to give visibility to French contemporary art, including abroad. French galleries have adapted to this new situation without changing their economic model. Everything then changed around the 2000s with the appearance of "mega-galleries" and the opening of branches outside their borders by Gagosian or Hauser&Wirth. This movement has gained momentum, which has disrupted the model inherited from Leo Castelli of an internationalization by network with looser links in which galleries collaborated with correspondents abroad. The ecosystem of French galleries has in fact completely changed in forty years with the investment in contemporary art by auction houses, the development of fairs, the increase in the number of collectors and... the Internet. In fact, it is the auction houses that are proving to be the main competition for galleries. But prominent French gallery owners do not hesitate to use the weapons of their rivals, including auctions, which allow the rapid rise of the rating of young artists. The difference in fortunes between human-sized galleries and mega-galleries is also obvious in the world of fairs, where the latter benefit in a regal way from the best locations compared to smaller structures when the latter have the chance and the honor of being accepted, which constitutes a strong sign of quality for the public. But things are changing because the fairs themselves are threatened in their essence due to the polluting image of the travel that is consubstantial with them. Nathalie Moureau distinguishes three types of players on the market according to their turnover, their presence in major fairs and the promotion that they manage to ensure for their in-house artists: flagship galleries, pivots and confidential ones. She nevertheless emphasizes that the latter also participate in the vitality of the market. The flagship role of Paris has remained preponderant since the eighties. The advent of the Pompidou Center, the revival of the Fiac, the opening of the Palais de Tokyo… Paris has become a more attractive place. Private institutions have multiplied and large international galleries have invested in the premises. The appearance of major private collectors such as François Pinault and Bernard Arnault has finally played a certain role in this regard. However, it is difficult for the economist to determine whether this emulation has benefited small galleries. It remains to be seen what the effects of the changes to the taxation system and the solidarity tax on wealth, the spectre of which is currently looming, have been for the entire market. The question of rents also explains the shifts made to Paris in favor of the three sectors: Matignon, Saint-Germain and especially the Marais. But it is now luxury hotels and auction houses that are in pole position. At the same time, the decline in museum finances since the 1980s and 1990s has led them to establish partnerships with galleries to balance the budget for many exhibitions. But this necessarily strengthens the capacity of mega-galleries to prioritize the promotion of their own artists. Quotas relating to the size of partner galleries would be a good thing in terms of fairness. Symmetrically, there is also the question of museums lending works to galleries, which is still prohibited today. Mega-galleries already have a number of assets to compete with museums. From exhibition space to guided tours, including artistic practice workshops, café-grocery stores, bookstores and shops selling derivative products and goodies. The temptation to position themselves as cultural institutions, research centers or even university centers is already beginning to emerge. Another major development: communication with, naturally, the development of digital technology and networks. On this point, Nathalie Moureau mentions the need to gain visibility through monumental works and events, but also the risk of letting reputation management slip away and seeing the media prevail over the artistic. Having become masters in the art of managing their editorial activity, mega-galleries are doing everything they can to become real brands. One question remains: what benefits do French artists derive from this rise in power of mega-galleries and medium-sized galleries enjoying good visibility? One thing is certain: unlike what happens in neighboring countries, French artists are underrepresented compared to their foreign counterparts in the overall offering of French galleries for international audiences. A sign of openness or an inferiority complex?

Illustrations: Nathalie Moureau

Figures of the new painting

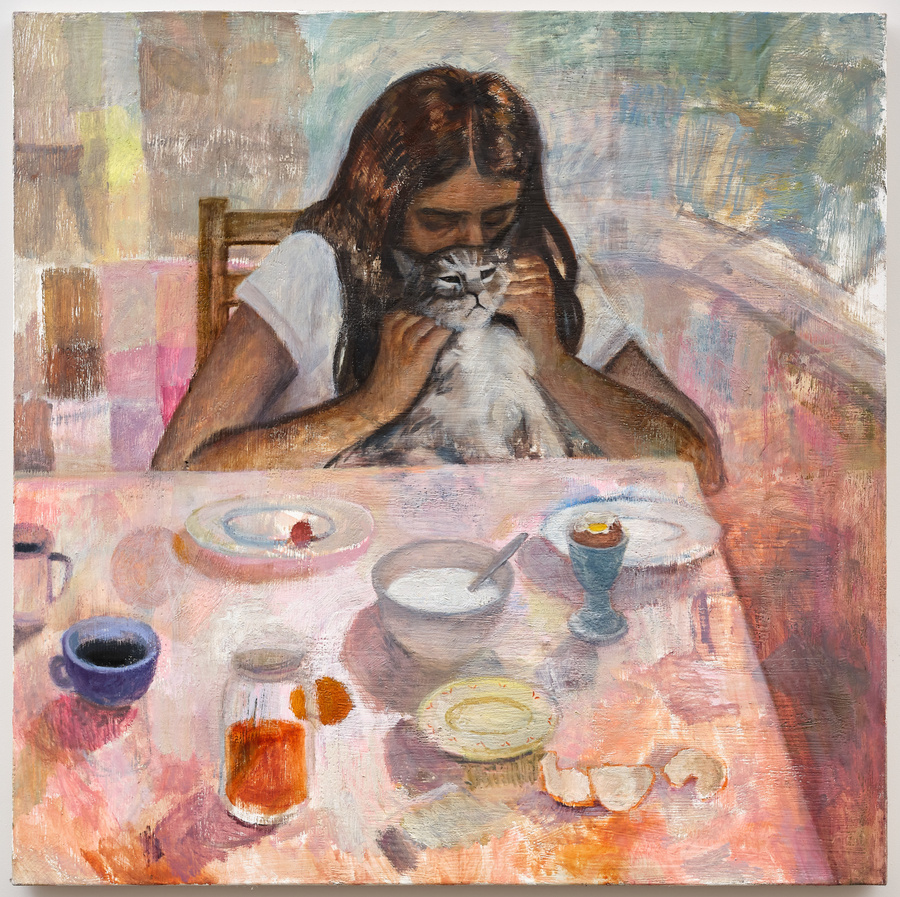

Between 2000 and 2020, painting and in particular figurative painting were considered old-fashioned by contemporary art. With rare exceptions such as the Urgent painting exhibition in 2001 and My Favorite thing! Painting in France in 2005 was a real crossing of the desert. Everything was photography, video art and post-Duchampian art. Today, it is its detractors of yesterday who are championing the return to grace of figurative painting. Art schools are getting back into it. Collectors are asking for more. The advent of Paris as the leading European place and the influx of collectors from all over the world who are mainly lovers of painting are not indifferent to the rise of "classical" painting in France. And museums have followed in the footsteps of galleries. The curated tours created by Art Paris naturally participate in the same movement of ennoblement as is also the case at the MO.CO. in Montpellier. One thing is certain, from a historical point of view, it would be good to put this forgotten painting through the sieve of a formal and theoretical analysis to identify the continuous lines of force between the day before yesterday and today. If only to avoid having the impression of reinventing painting with hot water. But what do today's young painters reveal about our times? Many self-portraits "more or less symbolic or realistic of a generation that is searching for itself" according to Art Press. The resilience of the medium is also brought to the forefront in its relationship to light and materiality. Like a refuge in the face of the rise of generative Artificial Intelligence. Leader of this new generation, dubbed by Pinault as much as by Orsay, Nathanaëlle Herbelin has distinguished herself by the dialogue that her painting establishes with works by Bonnard, Vallotton and Vuillard. A strange affiliation with painters who did not recognize a past. This "contemporanization", in the form of a stylistic reinterpretation of which many other examples flourish in the new generation, does not break any codes. What are the differences with Instagram images, Art Press wonders? The technical virtuosity of Jean Claracq, Romain Ventura, Laurent Prou and Adrien Belgrand finds favor in the eyes of this critic. It is "very personal and recognizable". The same goes for Marine Wallon and Clara Bryon who question the boundary between abstract and figurative. The "formal passion" of Dora Jeridi and Apolonia Sokol is also praised. Ultimately, it is on their differences that the emphasis should be placed, avoiding purely generational gatherings in which everything is mixed. If only to avoid any temptation of a simple fashion effect.

Illustrations: Nathanaëlle Herbelin (1989)

Emmanuelle and Efi, 2024

© Courtesy of the artist and the Galerie Jousse Entreprise/ Photo: Objets pointus/ © Adagp, Paris, 2024

Article written by Eric Sembach

Article written by Eric Sembach