Decoded for you in ART PRESS

The Unrepresentable

Themes selected in the dossier Painting the Unrepresentable

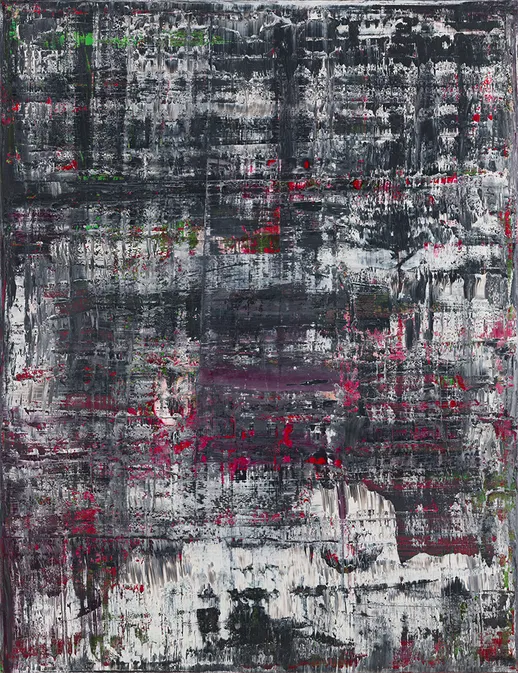

Can art seize horror without aestheticizing it? This is the question raised not by any artistic treatment of a documentary photograph but also by the public presentation of this photo itself. Respect for the victims and the refusal of voyeurism are naturally the two good moral reasons invoked to consider this type of iconography as taboo. The case of Thomas Hirschhorn's video Touching Reality, which showed montages of bodies mutilated in combat or attacks, was much discussed in this sense. The distance consubstantial with pictorial practice imposes the distance of withdrawal. This is why Gerhard Richter finally chose to transform his four paintings entitled Birkenau into abstract canvases by covering them, whereas Miriam Cahn can, without transition, move on to the distancing but raw rendering of a grotesque drawing.

The Birkenau series is one of the most controversial of all Richter's works, which have been widely discussed. And particularly in the book entitled Donner à voir that Éric de Chassey devotes to it. A witness in his youth to the rise of Nazism and then a disciplined and brilliant state artist of the GDR, Richter showed himself to be fascinated by the iconography of the concentration camps from the time he moved to the West in 1960. It was reading Images malgré tout by Georges Didi-Huberman that brought to his attention the clandestine photographs taken by the Sonderkommando of Auschwitz in 1944. It was at least their reproduction in the book that gave him the idea of reproducing them figuratively on a large scale to make images in the artistic sense of the term before realizing the futility of this approach. Richter's self-iconoclastic gesture of erasing the resulting figurative canvases to cover them with abstract strokes of color is not a total negation. In addition to their title Birkenau, they each retain an anchorage in reality by exhibiting while hiding their very origin. There remains an anchorage in reality. Éric de Chassey also underlines in his work the importance of the Grauer Spiegel formed by four square mirrors facing the paintings in their hanging at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. This device in fact makes it possible to refer not only to the Birkenau series but also, by changing the angle, to reproductions of the Sonderkommando photos that served as matrices for the paintings. It is these mirror games captured by cameras or selfies that are then the subject of moral commentaries from which the canvases distanced by abstraction are exempt. Idealized?

The representation of the tragedies of History holds an important place in Jérôme Zonder's work. For him, we inevitably come to deal with the limits of what can be represented as soon as we choose to speak out. We must then bring the whole world, the best and the worst, into a symbolic space. It is in this spirit that he brings forbidden images of the city of the Shoah into his series of drawings Chairs grises. The drawing precisely places at a distance and removes its realism from the image and gives it substance. In Zonder's aesthetic, this problem meets his reflection on the fictional character of Pierre-François, whose portrait he paints through the stories that construct him. He is crossed by the shimmering gray chaos created by gray areas of moving imprints that the drawing creates. But more than a distancing allowing the reactivation of images, it is here a question of activating the drawing. The search for the adequacy between the chosen writing and the desired sensation only intervenes in a second step. Love is the caress of two hands in the warmth of charcoal. Violence is a scene scratched with a thick graphite pencil. A dialogue is sought between the body of the draftsman and that of the viewer. Zonder's theory of art willingly draws its foundation from scientific bases. It is his reading of Changeux and Jeannerod that thus inspired his theory of the portrait of a character as the sum of the stories that construct it. As the eye perceives the thing and the brain makes it intelligible by "telling" it to us. His relationship to history is that of a child of the 20th century where the world has literally lost face through the horrors it has engendered in fifty years. After the announcement of the end of History, it is on television sets that genocides and the unleashing of hell have returned. Drawing is taking History into his own hands. Managing images as involving as those of the Shoah is not taboo for him. They must certainly be handled with extreme care, avoiding any "pornography" but in no case eluded because that would mean giving up speaking. Enlarging the image allows him to inscribe it in the gesture and at a good distance from the subject to whom the trace is preferred. Containing its impossibility, the action appears just from the point of view of a limit of representation. Like the blanks in Cézanne's painting, the space remains open in acceptance of the fact that certain things exceed it and represent its unrepresentability.

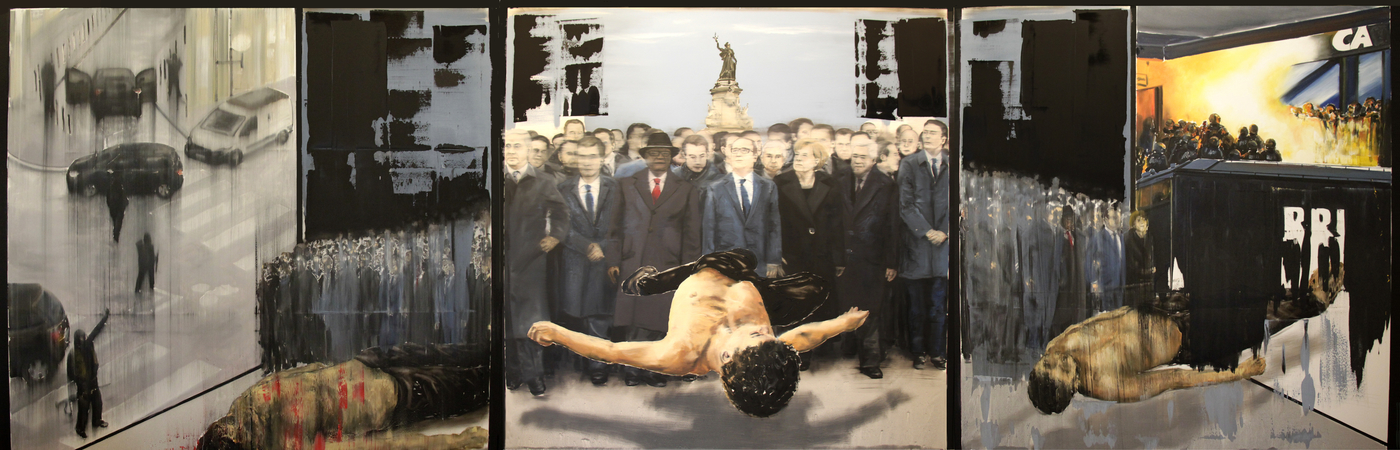

In Stéphane Pencréac'h's paintings, the "memorial" void becomes a sign when it is decoded as absence. It is, for example, what we imagine he misses that gives meaning to the deserted apartment in his painting Kfar Aza. We find ourselves in the next moment of History. In its mourning. History painting, however unrepresentable it may be, integrates into it in an abyss and in an implacable way a painting that bears witness to History. The toys are broken, the seats torn as a symbol of mutilated bodies, as a "spectacle of monstrosity". It is in the same spirit that Pencréac'h painted the Bataclan by opening its red curtain only on traces, black or red sketches of bodies littering a white space. For him, horror is represented modestly. Avoiding the pitfall of anecdotal or narrative painting makes it possible to create a universal image. The rarity of artistic images created in reaction to October 7, 2023 makes Stéphane Pencréac'h's work appear as an act of resistance to the rise of anti-Semitism. As Miriam Cahn did, because she was Jewish. The fact that she shows the bodies of victims does not shock Pencréac'h in the least. He grants her the moral and intellectual right to do so because she is wounded in her flesh for him. It is she that she shows. If we forbid, what can we show that deserves it? If we censor, how can we mourn? Cahn's painting is for Pencréac'h the best antidote to totalitarianism

Illustrations:

|

Birkenau de Gerhard Richter (2014)

|

Overview de Jérôme Zonder (2024)

|

Paris-11j anvier 2015 de Stéphane Pencréac'h (2017)

|