The birth of abstraction

Who invented abstract painting?

Kupka? Delaunay? Picabia? Or Kandinsky, as the official textbooks say.

The magazine l'Œil makes a strong case for itself by posing this fundamental question on the cover of its June issue. How can you miss it? It is clear from the statement alone that the answer will not be Kandinsky. Darn, we'll have to revise our history of early 20th century art.

It's a pity because we liked the anecdote that the great Vasily once and for all expelled the object to be represented from the canvas, preferring one of his stored paintings turned 90 degrees from its "normal" position. It was charming to think that painting had freed itself from the classical dictatorship of mimesis as a result of a simple shift of a figurative painting. Quite a symbol.

The carbon dating of works that could be the foundation stone of abstract art is not the only criterion for saying who was the first to walk on the moon of pictorial art. Who was the first brain to formulate the idea that you can make a painting out of nothing but shapes and colours? Because that is what painting is all about today.

In the 1910s, there was a whole host of theoretical texts written by Kandinsky, Kupka, Mondrian, Larionov and Malevich. These documents need to be taken into account today in the same way that we look at the photo of the finish of a horse race to see which horse crossed the line first.

|

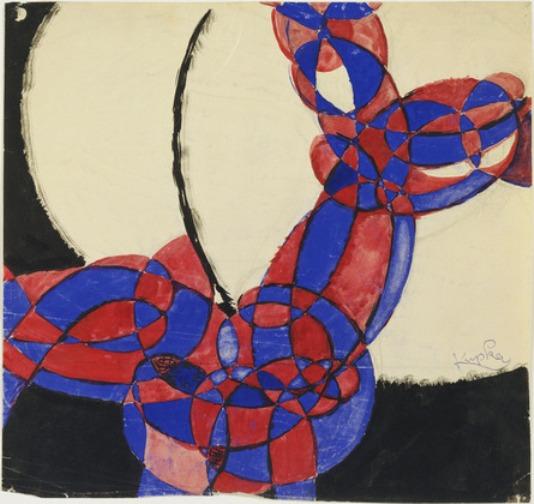

By the way, who invented rock'n'roll? Elvis, Chuck Berry or Ike Turner? On the basis of theoretical thoughts? It's hard to say. Well, it's even worse for abstract painting! Kandinsky seemed to lead the way when he followed the publication of his treatise on abstraction, The Spiritual in Art, with the exhibition of Composition V in Munich in 1911, surrounded by the group Le Cavalier bleu. This was followed in 1912 by Picabia with La Source, Léger with La Femme en bleu and Kupka with Amorpha. |

|

|

The positions seemed clear until Kupka mentioned an earlier work of his entitled Nocturne. But Picabia was quick to bring out a Caoutchouc from 1909 that was supposed to make everyone agree. Including the authors of backdated works. Atmosphere. This at least proves that everyone was aware of the importance of what had happened.

The death of the competing pioneers, the widow's war... then comes an era that we prefer to forget because it is a blot on the social record of the birth of abstract painting. The cult of the solitary founding hero of a movement greater than himself reaches its limit here. The cult of the solitary founding hero of a movement larger than himself reaches its limit. L'Œil invites us to detach ourselves from this in favour of a broader study of an intellectual context favourable to the emergence of new ideas. This context is also somewhat idealised in the official version that history has retained. The spiritual dimension inherent in the artistic approach of a Kandinsky, a Mondrian or a Kupka was eradicated in the process.

And now a Swedish painter by the name of Hilma af Klint emerges from this night of spiritualism. Problem: she seems to be beating everyone to the punch by taking the birth of abstract painting back to 1906. Look for the mistake: she was painting in search of the materialization of the soul and the sacred geometry of the universe. Not very compatible with "serious" abstraction

Who says worse? 1860! Fifty years before Kandinsky, a certain Georgiana Houghton, supposedly inspired by the spirits of Titian and Correggio, wanted to "restore the power of communion with the invisible" through her non-figurative painting. The incomprehension of the people of her century was guaranteed. This is enough to shake our current materialistic vision of abstract painting.

Textile creations and therefore minimized by the Bauhaus and Sonia Delaunay critics, sculptures and objects by Sophie Taeuber-Arp... Many other works left in the shade deserve to be associated with this great search for authorship of the origins of abstract painting.

All this is certainly true, unfair and even lamentable. But it is hard to forget this little story of the painting stored askew in the mythical studio from which everything would have started. There is something eminently pictorial about it. It is such a beautiful representation of the birth of abstraction.

Illustration:

- Vassily Kandinsky -Composition V -1911

- Frantisek Kupka - Amorpha - 1912

- Francis Picabia - The Source - 1912

- Fernand Léger - Woman in Blue - 1912