Guillaume Herbaut radiates

How can a photograph still emerge in 2021? Difficult, the bins of ephemeral sellers like Insta are full of pictures full of meaning and talent. If it is so difficult to break through, it now seems totally illusory to dream of lasting. Even as an amateur, being a photographic artist has become a difficult job.

Photographic reality

But now Art Press has taken Guillaume Herbaut out of the film bin in the fridge. His interview with Aurélie Cavanna is part of an issue that should be recommended to all those who love the camera. Between documentary photography and press photography, the reflection carried out through the magazine naturally probes the already porous and blurred frontier that we usually place between these two fields. It further blurs this blurred geography by adding art photography to the picture. You might as well say that there is a photo of photos in the end. All these pictures now competing for the same attention have no problem in themselves. Except for the much-maligned advertising photo. In fact, it is our gaze that is the problem. Our look, or rather our looks. Because we don't all see things the same way.

It's eye-watering

There are huge cultural differences today when it comes to reading images. The lowest common denominator among us has become the majority. And anything more than that is subjective. You have to be an alien to have the idea of appreciating a photograph not only for its own sake but also in reference to others that are all the more deserving of distinction. But so much the worse if these links and references are lost and, with them, what we must call the culture of the eye. Bringing Jonvelle and Balthus or Serrano and Toscani together is clearly too obscure a pleasure to be widely shared today. But that's okay. The eye is punctured but the eye is still hungry. And that's when the eye takes a look at the photos presented between the columns of Guillaume Herbaut's interview. It can't believe its eye.

And then the shock

We are on page 491. It is 6.10pm. It all starts with a silly photograph of a deserted cheap interior. But this is only a first impression. And this photograph is a real mille-feuille. So it's a false lead. We are rather in a spacious flat if one believes the depth of field punctuated by double doors which are not uncommon in student studios. The walls are uniformly white, which gives the scene a freshness. But also of softness because the struggle and the shadow between the light coming frontally from the third plane and laterally from the second is tinted by whole sections of the walls with a very beautiful pastel blue. Between the fade to black of the foreground and the radiant white of the background, a red armchair is enthroned. Slightly three-quartered and off-centre on the right of the picture, it faces us. As if it has been waiting for a long time to welcome a human with open armrests. That's it.

30220 microems

The problem is that the red armchair, so nice at first sight, is without its cushions. And a little out of shape. Its beautiful vintage red at first sight is in fact only faded red with rather kitschy golden patterns, symbol of an exploded bling-bling. And a self-celebrating daily life suddenly interrupted. For a door leaf is missing from the double door and there is rubble on the floor. Everything now looks a bit devastated. Looted? Why steal the cushions and not the chair? The machine for weaving links between image and reality multiplies the questions in order to freeze the meaning of the photo into a cliché. And to put it away to better forget it. But why is there the number 30220 discreetly written in red figures halfway up the right-hand side of the photo?

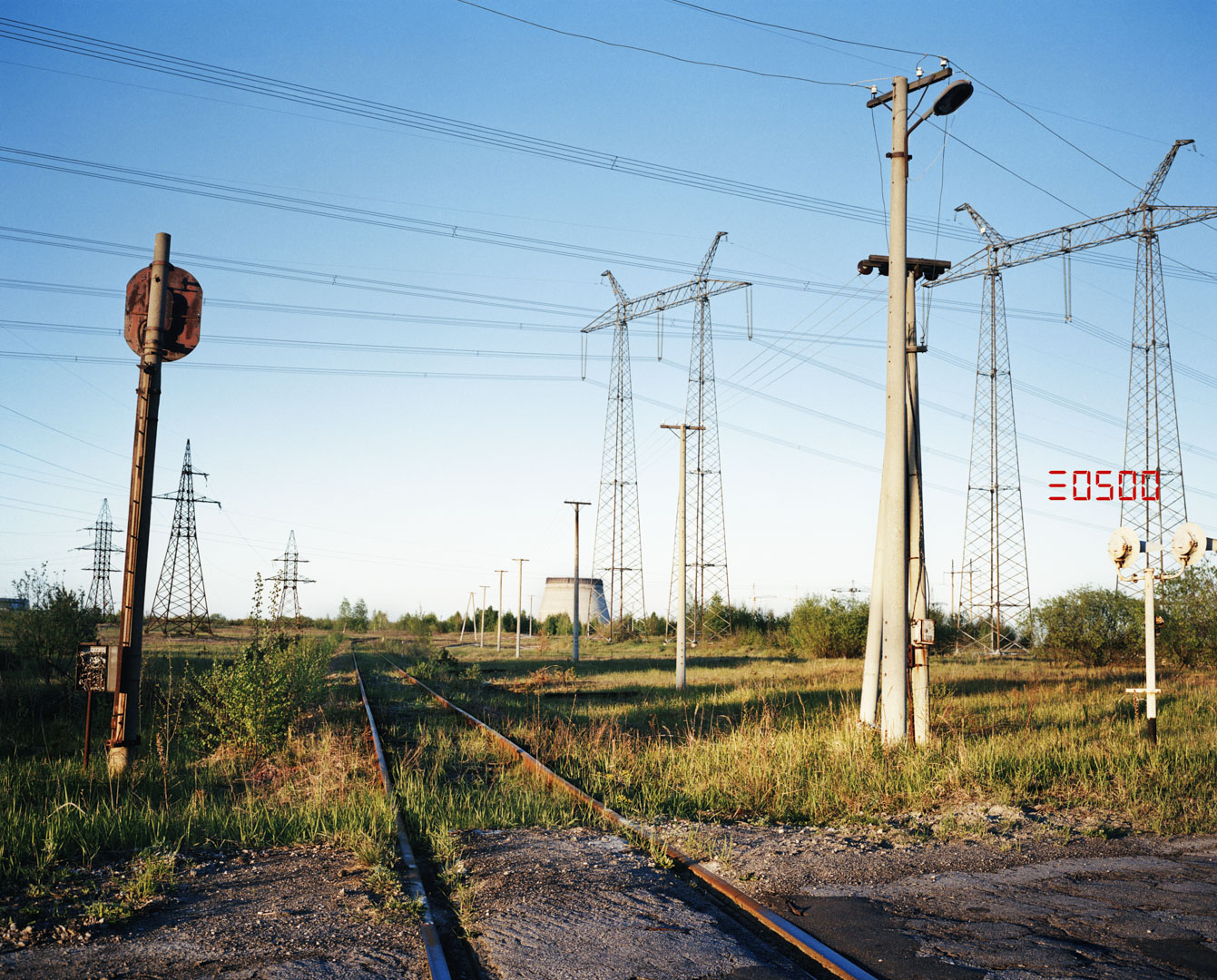

30220 is the level of radiation that prevailed in this Technobyl interior when Guillaume Herbaut photographed it as part of his series The Zone 2009-2011. This level of danger is measured in microems. As an indication, the norm is between 10 and 20 microems. The photograph radiates. In the age of geolocation, time stamping and facial recognition, this photo, already dated yesterday, still manages the feat of being fleetingly inscribed in our lives to disturb our minds even more the more clearly we see it.

It is, in a way, a documentary art photograph by Guillaume Herbaut.

Illustrations: The Zone by Guillaume Herbaut